Based on available literature, it can be inferred that hot flashes result from the body’s attempt to balance the fluctuations of estrogen as the reproductive system slows down. In historical discussions about the body, the term “humors” was often used to refer to the balancing of these fluctuations, as Ayurveda might suggest. According to Ayurveda (Frawley, 1999), every woman has a unique constitution or a blend of physical, mental, and emotional attributes known as prakriti, which results in the fact that each woman’s experience of perimenopause will be distinct. The combination of bodily humors known as vata, pitta, and kapha (the doshas), which are determined at the time of conception, form the prime material of life called prakriti. Before delving into the theory of doshas, it is important to understand a higher level of integration known as koshas.

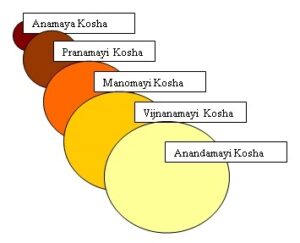

Theory of Koshas. Ayurveda seems to have originated during the post-vedic age outside of the Vedic Canon, and is indirectly related to the Atharva Veda (Feuerstein, 1998). The Atharva Veda discusses the koshas, which can be imagined as concentric levels between matter and spirit.

The anamaya kosha, located at the center and considered the densest level, represents matter and can be treated with curative techniques such as panchakarma and the use of herbs to cleanse the physical body. Panchakarma means five purification practices consisting of therapeutic enemas, purgatives, emetics, nasal medications, and blood cleansing which helps to eliminate excess ama from the body. Improper digestion can lead to the accumulation of toxins known as ama, which can promote disease, according to Svoboda (1999). During perimenopause, poor dietary habits and irregular routines can cause the buildup of ama, resulting in various symptoms. Additionally, ama can interfere with hormone function by obstructing their effects. Perimenopause at the level of anamaya kosha may result in hot flushes and physical stress reactions. If the stress is associated with hot flashes, the adrenals may respond by releasing hormones that produce sweating, muscle tension, rapid heart rate, increased blood circulation and vasodilation.

The anamaya kosha, located at the center and considered the densest level, represents matter and can be treated with curative techniques such as panchakarma and the use of herbs to cleanse the physical body. Panchakarma means five purification practices consisting of therapeutic enemas, purgatives, emetics, nasal medications, and blood cleansing which helps to eliminate excess ama from the body. Improper digestion can lead to the accumulation of toxins known as ama, which can promote disease, according to Svoboda (1999). During perimenopause, poor dietary habits and irregular routines can cause the buildup of ama, resulting in various symptoms. Additionally, ama can interfere with hormone function by obstructing their effects. Perimenopause at the level of anamaya kosha may result in hot flushes and physical stress reactions. If the stress is associated with hot flashes, the adrenals may respond by releasing hormones that produce sweating, muscle tension, rapid heart rate, increased blood circulation and vasodilation.

The next level represents vital air and is known as the pranamayi kosha. The respiratory life force at this level may be managed by breathing techniques called pranayama. Pranayama deepens and extends the life force, and has the effect of calming the mind and emotions, and increasing vitality. At the pranamayi kosha level, perimenopause can cause breathing constriction in women. Any form of constricted breathing reduces blood flow and decreases oxygen to the cells in various parts of the body. Somatic symptoms are partly due to lower levels of carbon dioxide, which increase the excitability of the nervous system.

The next level represents the mind and emotions and is known as manomayi kosha. The life force of the nervous system and senses at this level may be managed by yoga psychology. This involves control of mental fluctuations and mastery of consciousness according to Patanjali’s classical system of yoga. It is a practice that reveals the true self, leading to liberation through the eight limbs of yoga. The eight limbs of yoga are:

- Yama – Rules of social conduct;

- Niyama – Rules of personal behavior;

- Asana – Physical postures;

- Pranayama – Control of the vital force;

- Pratyahara – Control of senses;

- Dharana – Right attention or control of the mind;

- Dhyana – Meditation;

- Samadhi – Absorption.

Perimenopause at the level of manomayi kosha might result in anxiety or depression. Hormonal stress may exacerbate various psychopathologies, such as anxiety disorders, personality disorders, emotional disorders, eating disorders, substance abuse, mood disorders and so on.

The next level represents the brain and intelligence and is known as vijnanamayi kosha. The primary function of the intellect is to distinguish and arrange sensory information. However, if there is a lack of organization, it may lead to problems with memory. Perimenopause at the level of vijnanamaya kosha may also affect a woman’s ability to observe the intuitive and unconscious mind. As such, she may lose her sense of skillful action or the ability to choose appropriate behavior.

The next level represents the spirit and is known as anandamayi kosha. Hormonal stress at the level of anandamayi kosha might result in a loss of connection with a woman’s inner timelessness and sense of wholeness. The loss of this connection may affect a woman’s serenity and may compromise her joy as well as her ability to sense a connection with those around her. Hormonal stress may trap a woman in time, within boundaries, unaware of the higher stages of consciousness, resulting in suffering.

Health issues at the subtlest levels of consciousness are addressed by Maharishi Vedic Medicine, which unifies quantum physics and Ayurveda (Lonsdorf, Butler & Brown, 1995). Lonsdorf, Butler and Brown (1995) describe Ayurveda distinctly as the ability to access a unified field of consciousness to promote health. Quantum physics says that the universe is a participatory one where particles and waves are not necessarily distinct and separate from one another when viewed from a broader perspective (or consciousness). Quantum processes operating from levels of human physiology corresponding to such consciousness provide the ability to experience two opposing things at once, such as being sick and being well, through recognizing the particle and wave-like quality of matter. Lonsdorf, Butler and Brown (1995) state that, “While modern medicine treats and removes specific diseases on the structural, molecular, and biochemical levels, Ayurveda opens the deeper channels for the continuous flow of bodymind health primarily through unified field-level prevention techniques” (p. 55). Working through our thought processes, intelligence, emotions, behavior, and desires can lead to awakening the intelligence of nature within us to eliminate disease. Ayurveda affirms our bodies as biologically self-healing given the right lifestyle, exercise, diet, environmental and seasonal health practices. This is, of course, dependent on correct diagnosis of an individual’s “psychophysiology” (p. 58) or dosha as described next.

Theory of Doshas. The literature that forms the basis of yoga refers to balancing doshas for proper health (Feuerstein, 1998). In yoga and Ayurveda, the doshas represent three forces, or energies, that are condensations of the basic five elements of earth, air, fire, water and space found in life (Svodoba, 1999)

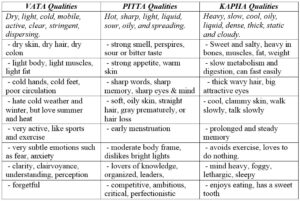

Vata (space and air). Vata dosha is cold, dry and irregular.

Kapha (earth and water). Kapha dosha is cold, wet and stable.

Pitta (water and fire). Pitta dosha is hot, oily and irritable.

Vata is also described as the energy of movement, pitta the energy of digestion or metabolism, and kapha the energy of lubrication and structure, according to Vasant Lad (see table below). Each constitution has all three interacting doshas in varying degrees.

In the basic constitution (prakriti) that each person is born with the degree of each dosha changes with development and environmental influences, according to David Sands, Associate Professor of Maharishi Vedic Medicine at the Maharishi University of Management (personal communication, June 02, 2002). Hormonal changes surrounding menopause are part of the developmental change from pitta to vata. If vata is the “mistress of menopause” (Svoboda, 1999) then pitta-vata would be the mistress of perimenopause.

In the basic constitution (prakriti) that each person is born with the degree of each dosha changes with development and environmental influences, according to David Sands, Associate Professor of Maharishi Vedic Medicine at the Maharishi University of Management (personal communication, June 02, 2002). Hormonal changes surrounding menopause are part of the developmental change from pitta to vata. If vata is the “mistress of menopause” (Svoboda, 1999) then pitta-vata would be the mistress of perimenopause.

Vasant Lad identifies seven body types:

- monotypes (V-P-K) where a single dosha dominates;

- dual-types (VP-PK-KV) which is the interaction of a combination of doshas; and

- equal types (VPK) where all three doshas are present equally.

The doshas are also represented during the lifespan as follows:

- kapha is the phase of childhood,

- pitta is the stage of womanhood and reproduction, and

- vata is the phase of life where menopause occurs.

Vata is in charge of kinetic energy, and during this phase kapha, the phase of childhood, which is in charge of lubrication and is a stabilizing energy, is in decline along with pitta, the phase of womanhood, which is the fiery aspect of transformation, i.e., digestion (Svoboda, 1999). As a woman moves away from pitta to the vata phase of life, she is in the transitional phase of pitta-vata, or perimenopause, regardless of her primary dosha imbalance.

Vikriti is defined as the elemental cause of one’s illness (Tirtha, 1998) and is dependent on environment, dietary habits, and relationships. Hormonal changes are not considered vikriti according to Dr. Fred Travis of Maharishi International University (personal communication, June 01, 2002). Travis concludes that a healthy transition through menopause would imply no depression nor anxiety, nevertheless there may be a concomitant vikriti if menopause is not managed correctly.

The theory of doshas may explain why women experience the climacteric differently. Vata produces fear when it is out of balance, as it is composed of space and air and is the subtle energy of movement. So anxiety might be a perimenopausal symptom for a vata type. Pitta arouses anger when it is out of balance, as it is composed of fire and water and governs body temperature. So hot flushes might be a perimenopausal symptom for a pitta type. Kapha produces lethargy when it is out of balance, as it is composed of the earth and water and governs bones, muscles, and tendons by holding things together (and it also acts like slow-moving glue). So, depression might be a perimenopausal symptom for a kapha type. This approach to understanding menopausal symptoms is not found in the literature, but it is an area for further study.

Pitta-Vata-Kapha Depression Styles

Depression is hypothesized to be the result of an overcharged emotional state in pitta-vata body types, according to Coppel (2002). Depression may be a symptom of doing too much or pushing too hard, thereby utilizing all the pitta energy to fire oneself up while exhausting the adrenals and the thyroid resulting in a depleted immune system (Coppel, 2002). Coppel calls this a pitta stress cycle which drains ojas, or root life force. Ojas maintains the integrity of every cell in the body, and is present in emergencies to bring forth the energy for healing. Coppel (2002) says depression results from ojas being constantly called upon and becoming depleted. She also connects depression with loss, which during the climacteric may result from the loss of female identity for some women.

Coppel (2002) describes the different qualities of depression that each female body type may experience from a western adaptation of Ayurveda. The vata type will worry and think anxiously. This may result in eating the wrong foods. A vata depression needs regularity in areas of diet, sleep and balanced thinking. Vata types tend towards circular thinking and they require the pitta fire to become more analytical and decisive. Vata types gain energy from less exercise as excessive movement is a problem with vata.

The pitta type will become angry or resentful, and due to a strong willpower and sense of right and wrong, she wants to be in control and will get depressed when she perceives things are out of control (Coppel, 2002). In light of the studies on locus-of- control and reaction to hot flushes, a pitta-vata type would want to control hot flushes and feel anxious or depressed if she couldn’t. The pitta type, when depressed, would need to lessen passion and energy output in order to avoid depletion.

The kapha type will be resigned to the situation and seek to avoid dealing with things in order to feel more grounded. She may avoid exercise and eat the wrong foods to deny her feelings. The kapha depression needs more activity and less, if any, daytime sleep in order to energize the fire of pitta. She needs to move a little faster, take on responsibility, speak out (not hold things in) and create more passion in her life.